Imagine a world without waste, where not just products but even buildings can be recycled. The prospect is perhaps closer than you might think. Faced with the climate emergency and resource shortages, companies, authorities and individuals everywhere are increasingly embracing ‘circularity’, finding ways to reduce the consumption of materials by sharing, recycling, reusing and repurposing.

In the construction industry, a host of trials, pilots and innovative new products are driving the shift towards a more circular approach to building. But the pressure for change is also rising: in 2022, CO2 emissions from construction and buildings rose to an all-time high of 40%, with building operations accounting for 27% and building infrastructure and materials for 13%.

“The size of these numbers equals the size of the opportunity,” says Kristin Hughes, director of resource circularity at World Economic Forum, “but it will be like turning a big cargo ship around. We will need a sustainable alternative for every material and a solution for managing every component.”

The World Economic Forum is working across the construction value chain to connect the dots in designing and overseeing more resilient, efficient, and more profitable businesses. For Hughes, as her title suggests, circularity is key to achieving this.

“When people hear circular economy, they often think it’s only about the environment, but it’s much more,” Hughes says. “Circularity is the solution to the sector’s massive footprint but also the key to finding new business strategies for a resource-constrained future.”

Necessity propels innovation

In the UK, Hughes cites a case where Covid-19 became a trigger for circular thinking. During the pandemic, supply chain disruptions and delays had been holding back business for a global engineering and development consultancy. So instead of waiting for materials like steel, copper wire, and electrical equipment, the company started searching locally for used and recycled alternatives.

“This was so successful that they are now looking for ways to normalize this approach and replicate it for cost efficiency and sustainability,” Hughes says.

Learning the circular way

“The mentality is definitely changing,” says Jean-Paul Bourgeat, senior vice president of KONE’s new building solutions. He says that for KONE, the move towards circularity has engendered new partnerships as the company co-innovates new processes and models.

“Recycling has been in place for years,” Bourgeat says. “The question now is how we move to a mature circular economy where dismantling and repurposing materials in new ways becomes possible, keeping in mind that reusing a component avoids having to produce a new one.”

One of the issues that needs to be overcome is that simply recycling an old piece of equipment or part of a building may not necessarily turn out to be as environmentally and resource friendly as it might first appear.

“For example, if you need lots of trucks to transport materials for recycling, that obviously has an impact on the carbon footprint,” Bourgeat explains.

The answer “probably lies in a localization of the reuse-repair-recycle approach,” he adds.

A recent pilot at the Opéra National de Lyon is a case in point. This 18-story architectural showcase, topped by an immense curved glass roof and built for crowds of up to 1,500 opera-goers, was being served by five elevators which were reaching the end of their life.

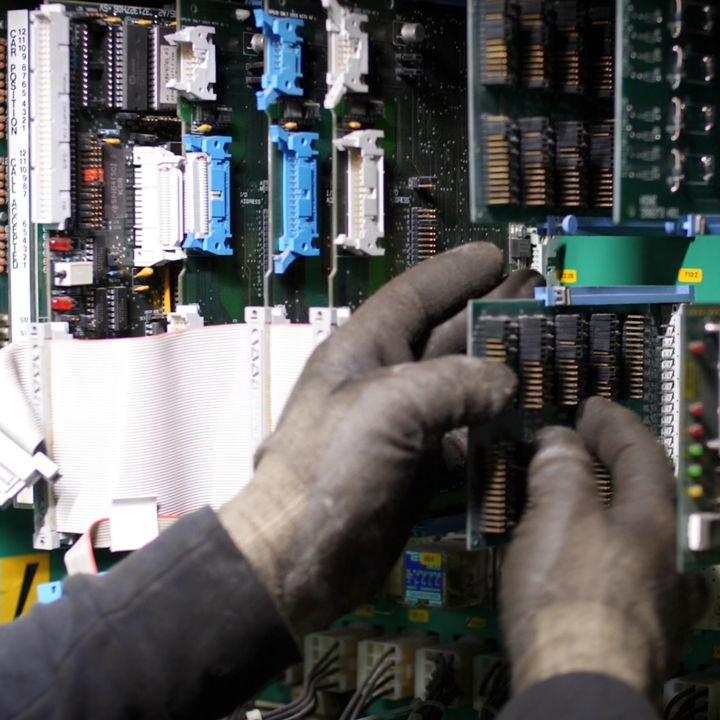

Working in partnership with the Opera and local online sourcing agents, the KONE team launched a historic dismantling and replacement process, where these elevators were meticulously disassembled, with 100 components identified for potential reuse, with the principle of excluding safety components.

Working around opera rehearsals and live performances, the team hand-collected and itemized materials ranging from ornate lamps to electrical boards, as well as more than three kilometers of cables.

Whereas normally each one would have been discarded as waste, many components were selected for a potential second life, and put up for resale to professionals in the real-estate and construction industries, and beyond.

Matching material availability with demand

The World Economic Forum’s Kristin Hughes is working with a start-up developing digital solutions to create markets for recycled resources such as those rescued from the Lyon Opera, by matching customer demand with resource availability.

Both Hughes and Bourgeat agree that for a truly successful circular economy, materials must be traceable, to ensure that buyers know where they have originated and how far they have traveled.

So-called digital ‘materials passports’ that capture and store information on construction materials are already in development, and could include RFID technology to track the whole product lifecycle. This is also intended as a way of increasing the industry appetite to take up these used materials.

Policy to boost progress towards circularity

Hughes warns, however, that policymakers are not always keeping up with industry strides towards circularity. She cites the example of cement, which accounts for a sizeable eight percent of all building materials emissions.

Hughes recounts the case of a building materials manufacturer which has developed a recycled cement product that performs as well as new cement, if not better, and has a considerably smaller footprint. But although the company is sourcing the used cement from Germany, Austria and France, legal constraints in those countries mean the recycled product can only be sold in Switzerland.

“So the company is left sitting on all this recycled cement and waiting for the legislation to catch up,” Hughes laments.

In the meantime, Bourgeat sees the construction business moving ahead in other ways: “We can already see a shift from a mindset of scrapping and rebuilding, which costs a lot more from a carbon point of view, to one of renovating, reshaping and repurposing, and we see our customers moving in this direction with us.”

While the infrastructure, processes and regulatory environment necessary for a full circular economy may still be a long way off, the direction of travel is clear and many elements are already in place for the transition to circularity. New KONE elevators, for instance, are overwhelmingly built of metal which means that 90% of components already have the potential for recycling or reuse.

Hughes wants to imagine a future where 100% of all end-of-life products could go back to their manufacturers for reprocessing, and where material-less business models would maximize the lifetime of buildings while addressing the problem of overconsumption and helping solve the climate crisis.

“Sometimes the simplest solutions are right in front of us,” she says.